Susan Ochshorn wrote an astute and important review of a new book on good practices in kindergartens around the country. I’m so pleased to have participated in this project and I’d love to share her review with you.

TEACHING KINDERGARTEN IN A NEW AGE OF ANXIETY

Posted by Susan Ochshorn, on March 7th, 2016 on her ECE Policy Matters blog – http://ecepolicyworks.com/teaching-kindergarten-in-a-new-age-of-anxiety/

These are dark times for the children in the garden. They have lost their place at the center of education. The shepherds of early development are struggling to move them in from the periphery. But the task is daunting, efforts thwarted in the age of standards-based accountability.

Teaching Kindergarten: Learner Centered Classrooms for the 21st Century breaks the silence—not a moment too soon. As editors Julie Diamond, Betsy Grob, and Fretta Reitzes note in the introduction, teachers determine what happens in a classroom, their voices critical for translating best practice to the uninitiated. Yet they’re experts in absentia, a rare presence at the policymaking tables.

A compendium of narrative accounts by early childhood educators across the United States, the book is, at turns, exhilarating and heart-breaking. I was riveted by these tales of young students, architects of their own learning. They’re the feisty, ingenious heirs of progressive philosopher John Dewey, moving toward complex understanding, and the “having of wonderful ideas,” in the words of educator and theorist Eleanor Duckworth. While the language of education reform—critical thinking, creativity, and innovation—may evoke this legacy, the prescribed methods these days for nurturing all of the above could not be more misguided.

Young children learn through exploration, inquiry, hypothesis, collaboration, and play in the messy, emotional arena of relationships with peers and adults. Progressive educators conceive of curriculum as organic, emerging from the interests of the child, primed to make sense of the world. They believe deeply in all children’s capability and intelligence. Teachers meet their students with love and respect, wherever they are on the path of development. The adoption of the Common Core State Standards, high-stakes testing, teacher evaluations based on student scores, and punitive actions against schools that demonstrate inadequate progress has disturbed this delicate ecology, changing the tenor and texture of life in the classroom.

Yet, the teachers persist. They’re determined to do right by the kids—holding fast to the rich theoretical base for their practice. Some have greater autonomy, like-minded supervisors giving them latitude. Others struggle to keep their courage in the face of anxious, overbearing administrators, narrow curricula, and conflicting claims on their space and time.

The book’s stories sparkle with the motivation, vibrancy, and pride of young learners. Katherine Clunis D’Andrea sees children as changemakers with a “voice.” A teacher at the Mission Hill School in Boston, she seeks the input of her kindergartners and first graders in a combined classroom including English language learners and students with special needs. After reading them Jeannette Winter’s book about Wangari Maathai, a Kenyan, the founder of the Green Belt Movement, and the first environmentalist to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, D’Andrea asks them: “If you were the president of the United States, what would you use your voice to do?” One youngster talks about installing speed bumps, another about making the city safer.

She then gets the children thinking about the possibilities for them, as five-, six-, and seven-year-olds. “What are you going to use your voices to do?” she asks. A question that launches days of long conversations, writing and drawing in journals, and, ultimately, the seeds for three projects to educate people about the importance of trees, recycling and endangered animals. D’Andrea had integrated nature into the curriculum, a “lush schoolyard” with raised gardens her youngsters’ learning laboratory.

When Dana Roth began her student teaching in New York City as No Child Left Behind had taken hold, disappointment set in. Everything she had learned about developmentally appropriate practice went out the window. Kindergarten, she writes, was “jam-packed with reading, writing, word work, and math…Where was the play? Where was recess? Where were open-ended investigations?”

Roth adapts to this new reality as best as she can, designing curriculum to meet the needs of all her students. Along the way, now ensconced at P.S. 10, in Brooklyn, she meets Renee Dinnerstein, a veteran early childhood educator and staff developer for the city’s public schools. In “Saim’s Wheelchair,” through a dialogue between the two women, we become flies on the wall, privy to the dynamic, fraught process of coaching and innovation.

Asked by the principal to introduce an inquiry approach to the school’s youngest learners, Dinnerstein starts work with Roth and her colleague, Karen Byrnes, in March. She predicts resistance to this intervention, so late in the year, her concern confirmed by Roth’s response: “Now what? “Our school day is packed with so much as it is. How can we possibly fit something new into our schedule?”

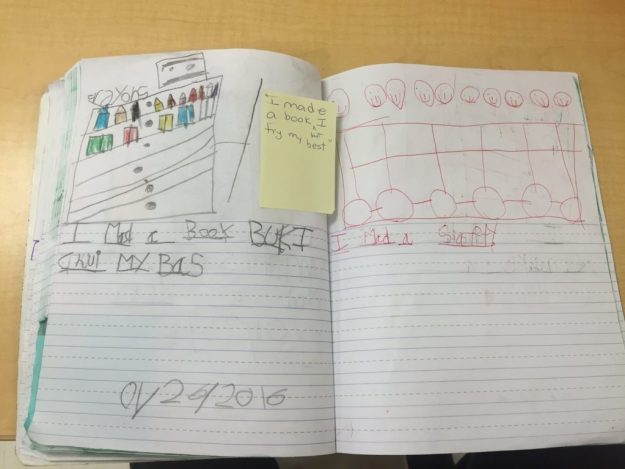

But the teachers sign on, transforming a transportation study into an opportunity for deep investigation tailored to the students’ emotional, social, and cognitive needs. A model of child-centered practice, as it’s known in the field. The account of their brainstorming is riveting. As Dinnerstein describes it, the two teachers were “fired up with excitement.” What were the opportunities for writing, they asked. What about collaboration and negotiation? How would the project help their students make sense of their world?

The study would include a trip to the local subway station, with sketches begun by the children in situ and revised in the classroom. But no sooner had the teachers embarked on the fieldwork than they realized that Saim, confined to a wheelchair, had no access. “How could we be so insensitive?” Roth writes. Yet, the faux pas opened a path to deeper inquiry and knowledge.

The result: a marvelous project, with Saim at the center, his cooperation having been secured. The class sits in a circle and sketches him, while he simultaneously works on a self-portrait. Roth and Byrnes begin gathering the children’s findings about wheelchairs. One day, at school closing, they observe Saim boarding the bus with the special door and platform, noting, too, the blue-and-white sign with the icon of a wheelchair.

The kindergartners also watch as Manny, a fourth-grader, negotiates this process on another bus, with his walker. Roth and Byrnes follow up, inviting him to their classroom for an interview, extending the children’s knowledge of disability and access. The children ask him how he uses his walker, if he can navigate with one hand, how he gets off the bus, if he can walk unaided, and if he took lessons to learn how to use his walker. “Kind of,” he says. “My therapists helped me. Do you want to try?”

As the study gets off the ground, Dinnerstein suggests rearranging the classroom to allow for more space for active learning. Soon, an observation center has sprung up, with measuring tape, magnifying glasses, paper, scissors, writing tools, and detail finders, the better for kids to zoom in on what they see. An old wheelchair has been procured from the custodian. Each child signs up to spend a day navigating the terrain on wheels. “The experience had a powerful impact on children’s development of empathy,” Roth writes. “They wanted to make our classroom more accessible for Saim or anyone else entering our room…”

“Teaching kindergarten is not for the faint of heart,” write Kelly D’Addona, Laura Morris, and Cynthia Paris in the book’s final story. A sobering account of facing “wolves”—as the teachers refer to the colleagues, families, administrators, and community members who challenge their practice.

D’Addona is all set to go with an activity that uses blocks to meet the objective of identifying and describing five plane shapes (circle, square, triangle, heart, and star). But her excitement wanes as her advisor declares it inappropriate:

She said the children would probably be too focused on building to identify and describe the shapes. She worried about my maintaining control…what children might do if I didn’t place a limit on how many blocks they could use. I was directed to lead an objective-based center in which students would simply identify and describe the five shapes. I should—and this made my heart sink—make sets of index cards with pictures of the shapes and have the children quiz each other…It went against everything I was taught about how children learn.

Paris, dirt under her fingernails after a morning building nests in the classroom, is called in for a chat with the first-grade team leader. She was failing to prepare her students for first grade, her colleague told her. “How frustrating and…painful,” Paris writes, “to be expected to teach in ways that violate deeply held convictions about what is best for children.”

Facing the wolves is risky, and frightening. But it must be done; the alternative is unacceptable. The authors of this chapter offer a set of advocacy lessons learned—a call to action to their peers on the front lines of teaching kindergarten in a new age of anxiety. May their brave efforts be replicated, along with their enlightened practice.

Is there a shift in the wind? Are teachers and parents finally fed up? Could the interest in my book on Choice Time indicate a return to joyful, age-appropriate, explorative learning?

Is there a shift in the wind? Are teachers and parents finally fed up? Could the interest in my book on Choice Time indicate a return to joyful, age-appropriate, explorative learning?

Two years ago I wrote a blog entry about an exciting, unexpected beginning- of -the- year study that merged inquiry, literacy and play. It’s not necessarily something that anyone would repeat since it came so naturally to my class that particular year. However it is an example of what the possibilities are when the teacher listens carefully to the children and feels free enough to run with the ball when the opportunity arises.

Two years ago I wrote a blog entry about an exciting, unexpected beginning- of -the- year study that merged inquiry, literacy and play. It’s not necessarily something that anyone would repeat since it came so naturally to my class that particular year. However it is an example of what the possibilities are when the teacher listens carefully to the children and feels free enough to run with the ball when the opportunity arises.

As the new school year approaches (or has already begun in some areas!) I thought I would share one part of the second chapter in my newly released book, published by

As the new school year approaches (or has already begun in some areas!) I thought I would share one part of the second chapter in my newly released book, published by  This image of a classroom with a voice guides our decisions about arranging the furniture and selecting the materials that will be waiting for the children on their first day of school. Even the simplest decisions can speak volumes. A terrarium placed at the eye level of a six-year-old, for example, says something very different than a terrarium placed out of reach on top of a bookshelf. When a classroom speaks, the message is obvious to all who pass through its doors. A classroom can say to each child:

This image of a classroom with a voice guides our decisions about arranging the furniture and selecting the materials that will be waiting for the children on their first day of school. Even the simplest decisions can speak volumes. A terrarium placed at the eye level of a six-year-old, for example, says something very different than a terrarium placed out of reach on top of a bookshelf. When a classroom speaks, the message is obvious to all who pass through its doors. A classroom can say to each child:

Some groups had changed the focus of their project by the time their week came up. That was fine!

Some groups had changed the focus of their project by the time their week came up. That was fine!

One evening last week I found myself, along with six other parents and teachers, sitting around a low table located in the basement classroom of a small Brooklyn cooperative pre- school. A candle, giving off peaceful aromas, was lit and we were all focused on the gentle-looking man at the head of the table. After introductions, he reached his hand upwards and grasped at an imaginary piece of the sky, explaining what happened when he did the same with a group of kindergarten children. “Can we bring back a small piece of the sky to share?” Without questions or doubts, the children caught the sky in their hands and carefully shared it with each other. This gentle man that I’m referring to is Richard Lewis, founder of the Touchstone Center in NYC.

One evening last week I found myself, along with six other parents and teachers, sitting around a low table located in the basement classroom of a small Brooklyn cooperative pre- school. A candle, giving off peaceful aromas, was lit and we were all focused on the gentle-looking man at the head of the table. After introductions, he reached his hand upwards and grasped at an imaginary piece of the sky, explaining what happened when he did the same with a group of kindergarten children. “Can we bring back a small piece of the sky to share?” Without questions or doubts, the children caught the sky in their hands and carefully shared it with each other. This gentle man that I’m referring to is Richard Lewis, founder of the Touchstone Center in NYC.

Can I let my teachers devote an hour each day for children to take part in inquiry-based choice time centers? Will my school still be able to maintain our high scores in reading and math? That’s the conundrum gnawing at the conscience of the very concerned principal of an early childhood public school in New York City.

Can I let my teachers devote an hour each day for children to take part in inquiry-based choice time centers? Will my school still be able to maintain our high scores in reading and math? That’s the conundrum gnawing at the conscience of the very concerned principal of an early childhood public school in New York City.

This coming fall

This coming fall